Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools have become indispensable in modern software development, promising to find vulnerabilities like SQL Injection, Remote Code Execution (RCE), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and XML External Entity (XXE) injection by analyzing source code. A core technique powering many SAST tools is data flow analysis, which tracks how data moves through an application, from potentially untrusted sources to sensitive sinks.

While these tools excel at analyzing the code you write, they often face a significant challenge: the vast ecosystem of standard libraries, third-party frameworks, and operating system APIs that nearly every application relies upon. When data flow analysis encounters a call to an external library function, say someFramework.processUserData(input), what happens next? Without specific knowledge, the library call becomes a "black box." The analyzer sees data go in, but does it know where that data came from if the library function introduces it? Does it know if the function sanitizes the data, passes it to another dangerous function, or simply stores it somewhere?

To achieve accurate and actionable results, static data flow analysis must incorporate knowledge about the behavior of these external library interactions. Ignoring them creates critical blind spots, leading to a frustrating mix of missed vulnerabilities and noisy false alarms.

Why Model? The Impact of Library Blind Spots

Failing to understand library behavior directly undermines the effectiveness of data flow analysis, primarily by causing false negatives (missed vulnerabilities) and false positives (incorrectly flagged issues).

Missing the Origin: Unrecognized Data Sources

Untrusted data – the starting point for many vulnerabilities – frequently enters an application through standard library calls. Think about reading HTTP request parameters (HttpServletRequest.getParameter), environment variables (os.getenv), file contents (Files.readString), or database results (ResultSet.getString). If the analysis engine doesn't recognize these specific library functions as sources of potentially tainted data, the entire data flow tracking process for that input might never even begin.

- Result: False Negatives. Real vulnerabilities originating from these sources remain undetected.

Missing the Danger: Unrecognized Sinks

Vulnerabilities manifest when tainted data reaches a sensitive operation, almost always performed via a library or API call. This could be executing a database query, running an OS command, rendering HTML, writing to a log file, or parsing complex input like XML.

- Example (XXE): An XML External Entity (XXE) attack occurs when an XML parser processes malicious external entities within an untrusted XML document. The sink isn't just any XML parsing call, but specifically calls like

DocumentBuilder.parse(taintedInput)made on a parser instance that hasn't been securely configured to disable external entity processing. If the analyzer doesn't know this specific method, under these specific configuration conditions, is an XXE sink, it cannot flag the vulnerability. Similar logic applies toRuntime.execfor RCE orStatement.executeQueryfor SQLi. - Result: False Negatives. The final, dangerous step in the attack chain goes unnoticed.

False Alarms: Unrecognized Sanitizers and Safe Transformations

Libraries are not just sources of danger; they also provide essential tools for security. Functions for HTML encoding, SQL parameterization, input validation frameworks, type casting, or secure configuration APIs act as sanitizers or safe transformations.

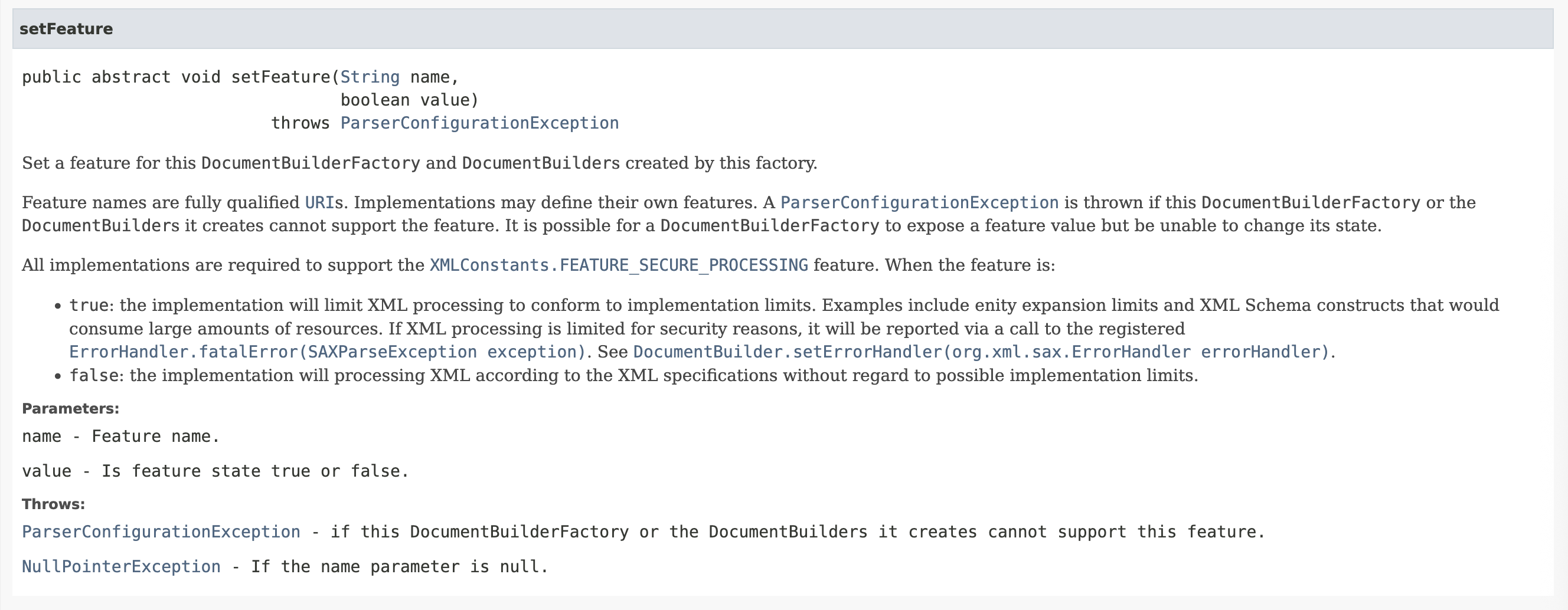

- Example (XXE): Java's JAXP library allows developers to disable dangerous XML features using

DocumentBuilderFactory.setFeature(XMLConstants.FEATURE_SECURE_PROCESSING, true). If the analyzer sees tainted data flowing toDocumentBuilder.parse(), but fails to recognize that the corresponding factory was securely configured earlier, it will incorrectly flag safe code. - Result: False Positives. Developers waste time investigating warnings about code that is actually secure, eroding trust in the SAST tool.

Broken Chains: Misunderstood Data Propagation

Data doesn't just appear at sources and disappear at sinks or sanitizers. It often flows through library functions. Consider StringBuilder.append, adding elements to a List, retrieving items from a Map, or simple utility functions like String.toUpperCase. If the analyzer incorrectly assumes data flow stops at these intermediate calls, or doesn't understand how data moves between parameters and return values (e.g., that appending to a StringBuilder modifies the object referenced by the input parameter), the taint chain gets broken prematurely.

- Result: False Negatives. The link between the source and the eventual sink is lost because the intermediate library propagation wasn't modeled.

What Needs Modeling? Key Library Behaviors for Data Flow

To overcome these blind spots, data flow analysis needs models that capture several key aspects of library behavior:

- Sources: Functions that introduce external or untrusted data, and which specific arguments or return values carry that data.

- Sinks: Functions representing sensitive operations, and which specific parameters are vulnerable if they receive tainted data.

- Sanitizers/Validators: Functions that neutralize taint or validate data, specifying the relationship between tainted inputs and safe outputs.

- Propagators: Functions through which data flows, defining the mapping between input parameters, object state, and return values.

- Configuration & State: Crucial for vulnerabilities like XXE, this involves modeling how calls to configuration methods (e.g.,

setFeature) alter the security posture of an object instance for subsequent method calls (e.g., makingparsesafe).

How Tools Model Libraries Today: Common Approaches

Static analysis tools employ various strategies to incorporate this essential library knowledge:

- Manual Summaries / Signatures: Often considered the most precise approach, tool vendors or security researchers write detailed models (sometimes called summaries, signatures, or specs) for specific library functions. These models explicitly define the source/sink/sanitizer/propagator behavior, often in a specialized language or configuration format. Think of them as expert-written "cheat sheets" for the analyzer. They require significant effort to create and maintain.

- Configuration Files: A simpler approach using configuration files (e.g., YAML, JSON) where users or vendors can list function names or patterns (using wildcards or regex) and classify them broadly as sources, sinks, etc. Less expressive than full summaries but easier for common cases.

- Stub Libraries: Replacing actual library bytecode/source code with simplified "stub" versions that contain only the necessary structure and annotations to guide the analyzer's data flow tracking according to the desired model.

- Pattern Matching / Heuristics: Less common for core modeling, but some tools might use simple code patterns (e.g., "if

setFeatureis called nearparseassume it's safe") as a fallback or complementary technique. This is generally less reliable than explicit modeling.

The Scaling Challenge and the AI Opportunity

While these modeling techniques work, they face a significant hurdle: scale.

The Manual Modeling Bottleneck

The sheer number of functions across standard libraries, popular frameworks (like Spring, Django, React, Express), and countless third-party dependencies used in modern applications is staggering. Manually creating, verifying, and maintaining accurate data flow models for all relevant library interactions is an incredibly time-consuming, labor-intensive process requiring deep security and library expertise. This bottleneck directly limits the coverage, accuracy, and up-to-dateness of many SAST tools.

Can LLM Bridge the Gap? LLMs for Library Behavior Reasoning

This is where Large Language Models (LLMs) present an exciting opportunity. With their growing ability to understand code structure, infer intent from function names and parameters, and process natural language documentation, LLMs could potentially revolutionize library modeling:

- Automated Classification: An LLM could analyze an API signature like

java.sql.Statement.executeQuery(String sql)and, based on its training data and the function/parameter names, infer that it's likely a Sink for SQL Injection, with thesqlparameter being sensitive. - Propagation Inference: For a signature like

java.lang.StringBuilder.append(String str), an LLM might infer that data flows from thestrparameter to theStringBuilderobject instance (a Propagator that modifies state). - Reasoning from Context: Analyzing configuration methods alongside usage methods could allow LLMs to generate models capturing stateful security behavior.

- Generating Summaries/Configuration: The output could be formatted directly into the configuration files or summary languages used by SAST engines, drastically reducing manual effort.

Example: LLM Reasoning about an XML Parser API

Consider this Java method signatures presented to an LLM:

// Hypothetical LLM Input: Analyze these Java method signatures package javax.xml.parsers; public class DocumentBuilderFactory { // Configures a feature on the builder public void setFeature(String name, boolean value) throws ParserConfigurationException; }

An LLM might reason as follows (conceptually):

"Based on the provided method signature and documentation, here's the semantic summary in the requested format:

F("javax.xml.parsers.DocumentBuilderFactory.setFeature:void(java.lang.String,boolean)", List((0, 0), (1, 1))),.

This indicates that for thesetFeaturemethod inDocumentBuilderFactory:

- The method takes two parameters (a String and a boolean) and returns void

- The taint flows from:

- Parameter 0 (the feature name String) to parameter 0 (the internal representation)

- Parameter 1 (the boolean value) to parameter 1 (the internal state)

This captures that both parameters affect the security state of the XML parser, particularly when dealing with security-sensitive features likeXMLConstants.FEATURE_SECURE_PROCESSING."

The Road Ahead

This AI-driven approach is still emerging. Significant challenges remain around ensuring the accuracy and soundness of LLM-generated models, handling complex or poorly documented APIs, verifying the output, and integrating it seamlessly into existing SAST workflows. However, the potential to leverage AI to overcome the manual modeling bottleneck is immense and could lead to substantial improvements in the scalability, coverage, and ultimately, the effectiveness of static analysis tools.

Closing Note: Smarter Analysis Requires Understanding the Ecosystem

Static data flow analysis is a powerful technique for finding vulnerabilities, but it cannot operate effectively in isolation. Real-world applications are complex ecosystems built upon layers of libraries and frameworks. Accurately modeling how data interacts with these external components – identifying sources, sinks, sanitizers, propagators, and crucial configuration states – is not just beneficial, it's essential for minimizing both false positives and false negatives.

While manual modeling provides high precision, it faces scaling challenges. The future likely lies in a synergistic approach, combining expert human insights with AI/LLM assistance to generate and maintain library models more efficiently. When evaluating or implementing SAST solutions, always consider how external library interactions are handled – it's often the key differentiator between a noisy tool and one that delivers truly actionable security insights.

Explore Call Graphs with AI Assistants

Understanding data flow and library interactions requires deep knowledge of your codebase's call graph – exactly what the Code Pathfinder MCP Server provides. Now you can query your codebase's call graph directly through AI assistants like Claude Code, Codex, OpenCode, or Windsurf using natural language.

Ask questions like:

- "What functions call this database query method?"

- "Show me all callers of the sanitization function"

- "Trace the data flow from user input to this sink"

- "Find all functions that depend on this library call"

The MCP (Model Context Protocol) server provides semantic code intelligence including:

- Deep call graph analysis to trace function dependencies

- Symbol search with metadata about parameters and return types

- Import resolution to understand library usage patterns

- Multi-project support for analyzing microservices architectures